Forward-looking: There's an exciting new cancer treatment on the horizon called Flash radiotherapy that could shake up the field as we know it. Rather than delivering radiation over several minutes like current techniques, Flash supercharges traditional radiotherapy by blasting tumors with an extremely intense dose of radiation in under a second.

While it may not sound like a major leap, this approach offers one big advantage: killing cancerous cells while doing less damage to surrounding healthy tissue. This is believed to occur because healthy tissues can better withstand the rapid dose than cancer cells.

Early experiments on healthy lab mice are promising and have already proven that the rodents don't develop the typical side effects, even after two rounds of radiation.

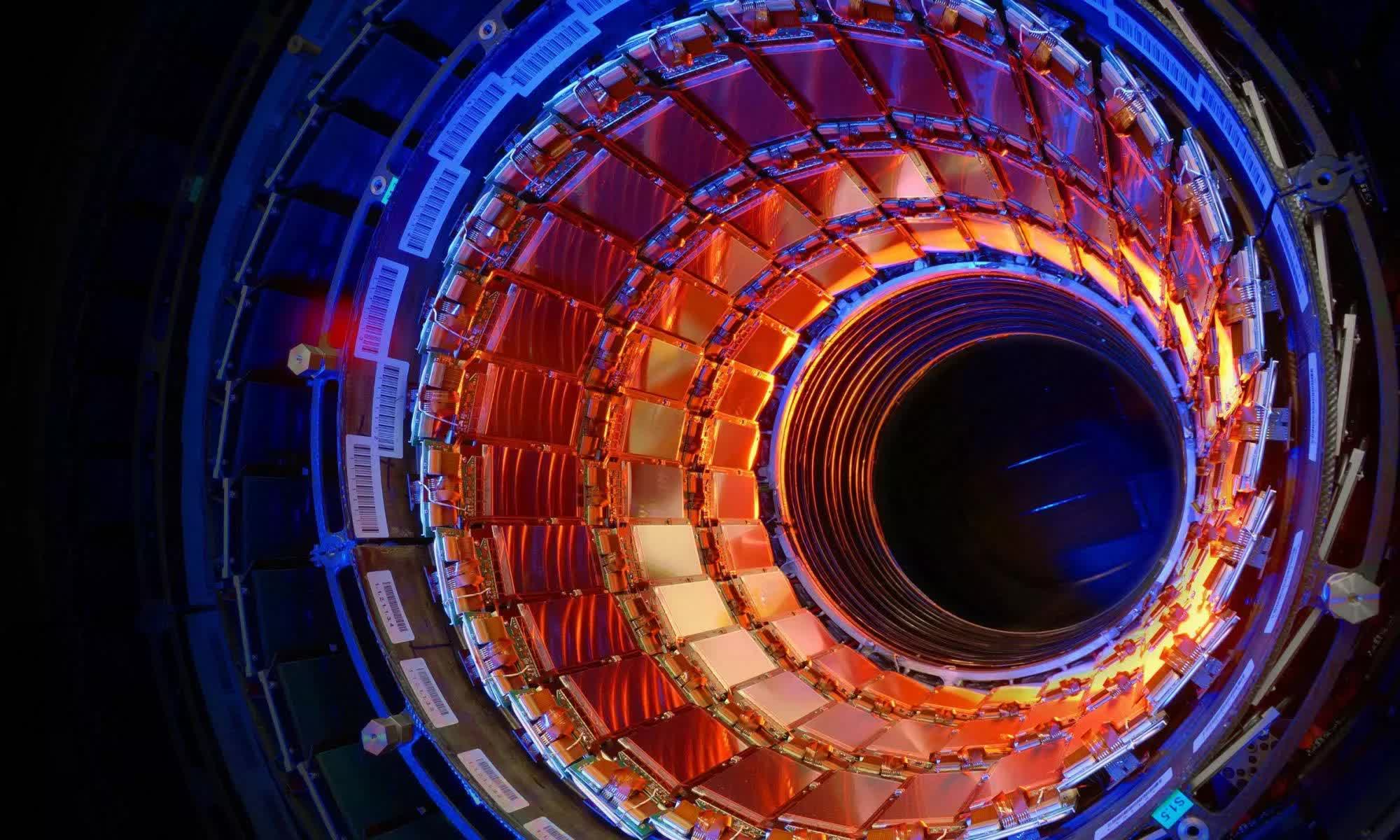

The work behind Flash radiotherapy is being bolstered by an unlikely source: CERN, the particle physics lab famous for the Large Hadron Collider. While the concept of Flash originated from radiobiologists over a decade ago, CERN is adapting its particle accelerators – originally designed for smashing atoms – to deliver radiation at ultra-high speeds for cancer treatment

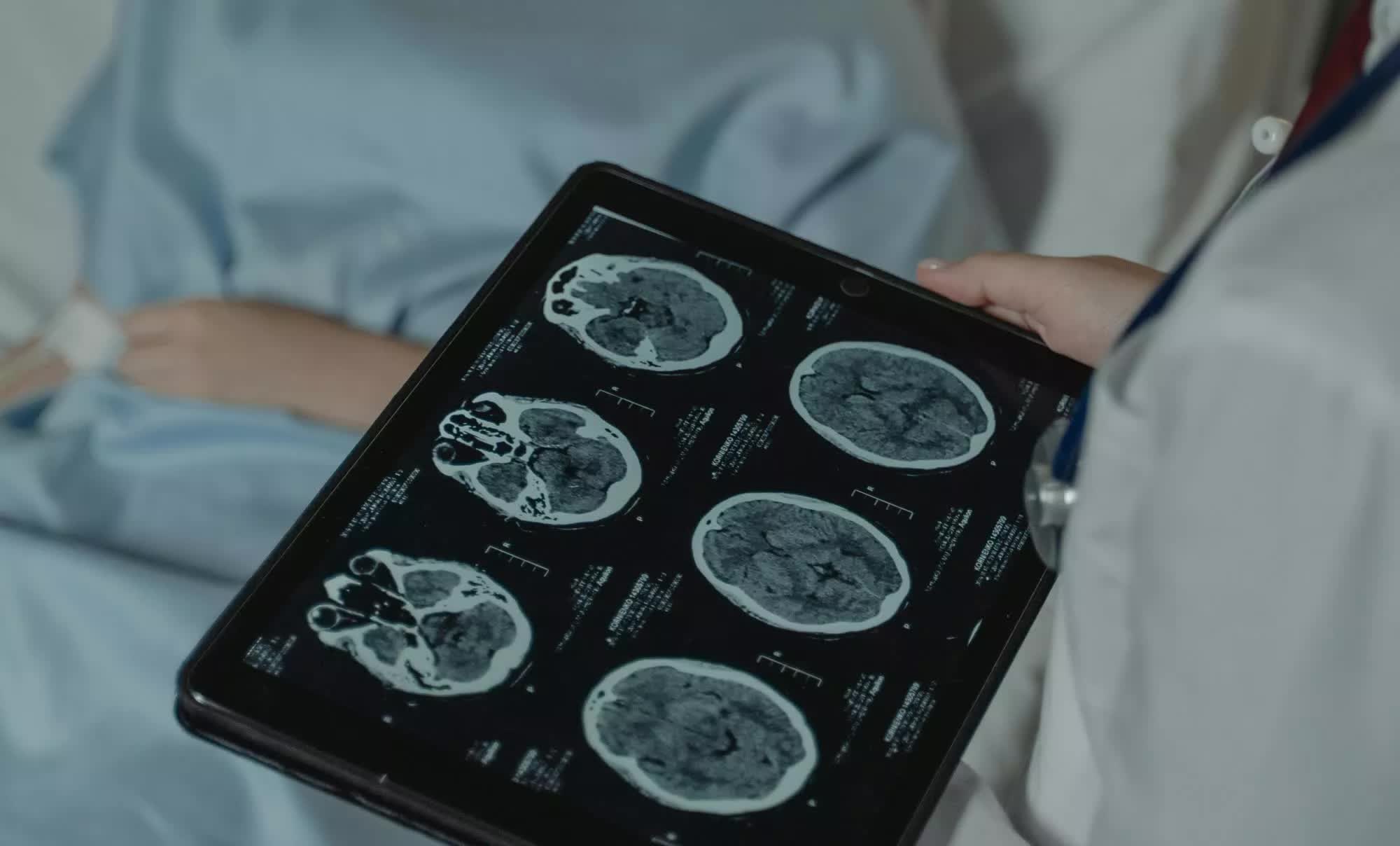

Billy Loo, who runs the Flash lab at Stanford University, stated to the BBC that Flash produces less normal tissue injury than conventional irradiation without compromising anti-tumor efficacy. This would prove especially useful for treatments aimed at more delicate areas, like the brain, which is typically treated at a high cost.

As Dr. Marie-Catherine Vozenin from Geneva University Hospitals explained to the BBC, "We're able to cure kids with brain tumors, but the price they pay is high – things like lifelong anxiety, depression and significant loss of IQ."

If successful, Flash may allow higher cure rates for notoriously deadly cancers like glioblastoma brain tumors.

Flash could also allow higher radiation doses to tackle tough-to-treat cancers that have spread to other organs. With conventional radiotherapy, doctors often can't go as far as they'd like over fears of collateral damage. But Flash could make more aggressive treatments viable.

Human trials of Flash are already underway at various hospitals around the world. For instance, the Cincinnati Children's Hospital in Ohio, US, is planning an early-stage trial involving children with metastatic cancer that has spread to their chest bones.

For now, most of these treatments are using protons as the radiation particle since proton therapy machines can be adapted for Flash delivery. But researchers are also exploring other particles like carbon ions and electrons.

Once human trials prove fruitful, addressing accessibility will be another challenge. Equipment required for such therapy is massive in size and hugely expensive, limiting its availability to more sophisticated hospitals. Carbon ion therapy hardware can even be building-sized.

Making Flash cheaper and improving accessibility is a challenge CERN is working on by collaborating with hospitals and companies. The ultimate goal is to make it possible for any hospital with radiotherapy equipment to provide Flash.

There's still a lot of research to be done, of course, and the risks of Flash are being studied. But the early signs are enough to get oncologists excited.